The headlines today--or any day--reinforce the tragedy of life on this planet. Hundreds Feared Dead After Boat Filled With Migrants Capsizes. Video Purports to Show ISIS Killing Ethiopian Christians. There are ample reminders of the world’s calamity, horror and heartache in our daily social media feeds.

The ubiquitous reporting of tragedy can sometimes desensitize us to it. Art, with its audacious capacity to bring meaning out of the meaningless and (sometimes) beauty out of the ugliness, can re-sensitize us. "The role of an artist is to not look away"-Akira Kurosawa one said. And though what their cameras or brushstrokes capture may not make us comfortable, the artist’s gaze is crucial for the building of humanity’s awareness and empathy.

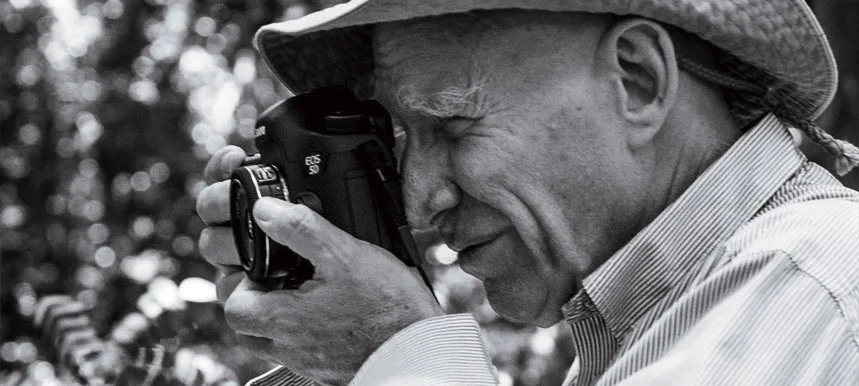

The Salt of the Earth, a new documentary about photographer Sebastião Salgado, powerfully shows this. Directed by Wim Wenders and Salgado’s son, Juliano, the film chronicles the journeys of Salgado to capture the struggle of humans in the midst of war, disease, poverty, famine, industry, migration and more. Over his four decade career, Salgado’s images brought him much acclaim but they also brought awareness to the plights of many. His gaze definitely manifests a “not looking away” boldness but also a humane compassion. There are lessons here in how to see, and why seeing well matters.

As I finished the film I kept thinking of the Matthew 9:36 verse where it says of Jesus that, “Seeing the people, He felt compassion for them.” Had Jesus been given a camera in the 1st century, I imagine his portraits would look not dissimilar from Salgado’s. Salt of the Earth sees a lot of horrific things but it always sees them through a lens of compassion and, ultimately, hope.

As chroniclers of reality and human suffering, artists are often prone to falling into despair and giving up on people. Salgado certainly is tempted by this, especially after his time in Rwanda in the mid-90s, photographing unspeakable evil in the midst of the genocide. Following this, his career turned toward nature and animal photography, capturing the beauty of the earth and its Edenic majesty, apart from the hellish wars and struggles of mankind. Yet ultimately the beauty of the natural earth and that of mankind are inextricable; humans are the caretakers of the Garden, after all, the stewards of creation for good or ill.

Recognizing this, Salgado decides do his part as a human steward and preserver of God’s creation (“Salt of the Earth” is a metaphor that implies a preserving function). He re-plants a rainforest in his Brazilian hometown, a forest that had thrived in his childhood but a half century later had been decimated by famine and industry. Salt of the Earth--so much a film about decay, inertia and fallenness--ends on a beautifully hopeful note as the “garden” of Salgado’s upbringing is replenished and brought to new life. Resurrection.

Among its many merits, Salt of the Earth is a beautiful reminder that having eyes to see the evil and deprivation of our world should not lead us to apathy and despair, nor complaining and rage. Our response should rather be to recover our original Edenic calling: to bring order out of the chaos, to combat evil through love, to plant seeds of new life in every sphere, to be the salt we were created to be, agents of preservation in a world stricken by decay.